THE STORY OF FRANK CONRAD AND HIS GARAGE WORKSHOP

By Richard J. Harris, Jr.

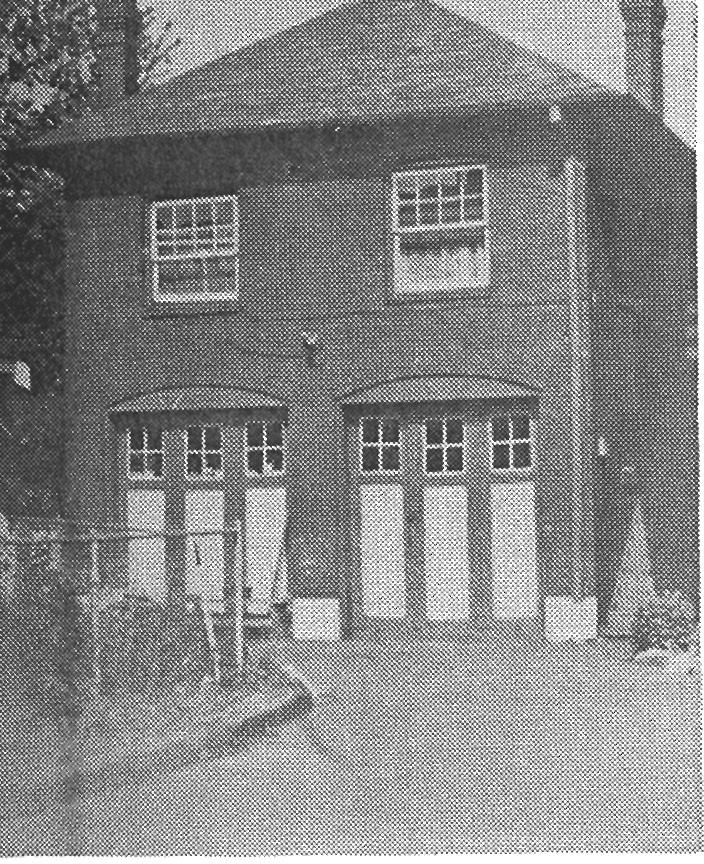

Thousands of people pass by it every day. Most don’t even know it exists or understand its importance. Yet the old, red brick garage still stands–nearly seventy years after it became a world-famous birthplace. A short distance away, in a clump of weeds, a sunken, tarnished plaque proclaims, “Here Broadcasting was Born.”

Indeed it was, fathered by Westinghouse engineer Frank Conrad in the small second-floor garage workshop of his home in Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania.

To look at the garage today, you might never guess that out of these walls came a concept that completely changed the world.

But who was Frank Conrad and what did he do that sets him apart from other early radio experimenters? Why, to this day, do his achievements go largely unrecognized while the work and the workshops of the more “well-known” inventors are preserved in museums?

Frank Conrad was born on May 4, 1874 in Pittsburgh. He attended school locally but at age 16 he left to work for Westinghouse as a bench-hand. His inventive talents were quickly recognized and he advanced in position with the company. He eventually became chief engineer at the East Pittsburgh works (his official title was always Assistant Chief Engineer out of respect for a predecessor.) Although his expertise spanned across a number of engineering fields, it was through radio that he would change the world.

Conrad first became interested in radio in 1912 when, to win a wager on the accuracy of his watch, he built a radio to receive time signals sent out by the Naval Observatory in Arlington, Va.

In 1916 he built a transmitter and began operating an amateur radio station. Licensed as 8XK, it was to become the world’s original “broadcasting” station and the direct forerunner of KDKA.

Although amateur radio operations were banned during World War I, Conrad worked on communication equipment for the military and received special permission to conduct tests over the air.

In 1919 the ban on amateurs was lifted and Conrad became one of the best-known amateurs in the country.

Frank Conrad about 1940.

(Photo at the top of this page is courtesy of the author.)

That year, to save his voice from endless hours of talking into the microphone, he substituted a phonograph and played a musical record over the air. The results were astonishing. He soon began receiving numerous requests through the mail. A typical letter might ask him to play a certain song at a certain time so a listener could convince some skeptic that music could be transmitted through the air.

The interest in Conrad’s musical programs was so great that he told his listeners that he would establish a regular schedule of musical “broadcasts” two nights a week.

Conrad’s garage about 1950 is shown at the top of this page. (That photo is courtesy of the author, Richard J. Harris, Jr.)

The idea of playing music over the air was not new. It had been done as early as 1906. What was unique was this word “broadcast,” given new meaning by Conrad to describe the idea of transmitting only to an audience of listeners. Until that time, radio was seen primarily as two-way communication between transmitting stations–a sort of “wireless telephone.” This pioneering concept of “broadcasting” meant that radio could become a medium of information and entertainment for the general public. Its possibilities were limitless.

Limited, however, was Conrad’s supply of phonograph records, so he took his dilemma to a music store owner in Wilkinsburg. The owner, aware of Conrad’s broadcasts, was happy to lend him all of the records he could use with the stipulation that the listeners be told where the recordings could be purchased. Conrad agreed and the store owner soon discovered that records played over the air sold better than others. Thus the “commercial” aspect of broadcasting was born and to this day it remains the foundation of the entire industry.

By 1920 a clearer picture of broadcasting was beginning to take shape but Conrad’s audience was still largely made up of amateurs and technical-minded people who had constructed their own receivers. If broadcasting was to be available to everyone, more radios would be needed. Realizing this, the Joseph Horne Company, a Pittsburgh department store, ran the following ad in the SUN on September 29, 1920:

Air Concert “Picked Up” by Radio Here

Victrola music, played into the air over a wireless telephone, was “picked up” by listeners on the wireless receiving station which was recently installed here for patrons interested in wireless experiments. The concert was heard Thursday night about 10 o’clock, and continued about 20 minutes. Two orchestra numbers, a soprano solo–which rang particularly high and clear through the air–and a juvenile “talking piece” constituted the program.

This ad helped make Westinghouse officials, led by Vice President H. P. Davis, realize that a tremendous business opportunity lay in the construction of a radio station and in the manufacturing of receivers for the general public. Work on a transmitter, to be stationed in East Pittsburgh, was begun immediately. At the same time application for a radio license was filed and on October 27, 1920 the station was licensed as KDKA. Chosen for the new station’s premier broadcast would be the Harding-Cox presidential election on November 2nd. This famous broadcast, of course, became an overnight national sensation.

Certainly the direct product of Conrad’s radio work was the establishment of commercial station KDKA, but every radio station, every television station–the entire broadcasting industry–owes its existence to Conrad’s concept of broadcasting, pioneered in his little garage workshop in Wilkinsburg.

Conrad’s accomplishments were not limited to radio. A prolific inventor, he obtained more than 200 patents in a variety of fields. He has been characterized as a quiet, unheralded and often overlooked genius, whose achievements rank with more familiar inventors like Edison, Bell, and Marconi. His contributions certainly place him among the greatest inventors of this century. To illustrate this, Si Steinhauser related the following story in a 1970 Pittsburgh Press article on Frank Conrad:

The same little, old gentleman [Conrad] had gone to London to a conference of world electrical engineers. He took along a homemade radio receiver built in a small suitcase. There in his room at Grosvenor House he asked the great Marconi to examine the set and to estimate from what distance it might pick up a broadcast. Marconi looked at the set minutely, shrugged his shoulders and said, “You can pick up sound from a distance of 15 miles.”

The little, old man reached in his trouser pocket, withdrew a spool of ordinary copper wire, attached one end to the antenna post on the set, threw the spool out the window to unwind, turned on the set and picked up KDKA, more than 3,000 miles away.

Frank Conrad died on December 11, 1941. He inspired a communication revolution that dramatically changed and continues to change the world we live in. His concepts and inventions touch our lives every day. Yet most people have never heard of Frank Conrad. Some type of permanent, lasting tribute to him is decades overdue.

Alice Sapienza-Donnelly, who saved Conrad’s workshop from demolition in 1972, the Pittsburgh Antique Radio Society, and I have been planning a commemoration of Conrad’s life and work. Our goal is to salvage or recreate his radio equipment and to preserve his garage workshop as a “Birthplace of Broadcasting” museum which, we hope, will establish this belated memorial.

Sources: Conversation with Alice Sapienza-Donnelly. It Started Hear (KDKA’s 50th Anniversary publication), KDKA, 1970.

Steinhauser, Si. “Frank Conrad…A Friend’s Story Of A Radio Pioneer”. The Pittsburgh Press, October 18, 1970, pp58-61. Sources

Get Involved

PARS needs you! Every member must consider how they can make a contribution to the future of PARS. Can you mak a presentation at a meeting? Can you help with the auctions? Write an article for the Oscillator? Write a blog post on this web site? Chair a committee to get a specific project done? Or just add your comment to any blog post on this web site so that it become a more interesting discussion. You CAN help. Speak with any club Officer or Board Member to volunteer your support! Do it TODAY!

PARS Meetings

Most meetings are held at the Brentwood Presbyterian Church basement hall located at 3725 Brownsville Road, Pittsburgh 15227. Check the NEWS & EVENTS page on this site for the current meeting schedule.

PARS Special Events

Two of our annual events do not happen at the Church. The Tri-State Radio Fest, PARS' biggest event of the year, is held each April at the Center Stage Banquest Hall at 1495 Old Brodhead Rd, Monaca, Pennsylvania 15061. The PARS Annual Radio Picnic is held each July in North Park, generally at the Roosevelt Pavilion if we can get it. These two events plus our annual holiday luncheon at the church are PARS' best-attended events of the year. Please see the NEWS & EVENTS page for this year's specific details.

PARS Officers & Board Members

Bob Knowlton, President - [email protected]

Vice-President (OPEN)

Jeff Pleva, Treasurer - [email protected]

Chris Wells, Secretary - [email protected]

Andy Manko, Board - [email protected]

Ed Kaczkowski, Board - [email protected]

John Busalaachi, Board - [email protected]

Joe Patrick W3KWZ, Editor of The Pittsburgh Oscillator (PARS Quarterly Newsletter) - [email protected]

Rex Kraeuter, Club Historian & Publications Manager- [email protected]

James Stevens, Webmaster - [email protected]

PARS Volunteers

As with most hobby clubs, PARS is entirely staffed by volunteer Officers, Comittee Chairmen and Board Members. New volunteers for these positions are always welcome. To contact any of the current slate of officers and Board members, please see the ABOUT PARS page elsewhere on this web site.

NOTICE: This web page and this entire web site including all photographs, text and content is copyright 2019-2024 by The Pittsburgh Antique Radio Society, Nothing on this web site or in our newsletter The Pittsburgh Oscillator may be republished in any form without the express written consent of a PARS Officer or Board member. Permission must be sought and granted in advance of publication and proper attribution to PARS must appear on the same page, on the same screen or video segment in such a way that it occupies the same space as the republished PARS information. See the ABOUT PARS page for PARS contact information.